Vancouver, renowned as one of the world’s most prestigious and expensive cities, is a jewel in Canada’s crown. However, it also hosts the Downtown Eastside (DTES), the country’s poorest neighbourhood. Notoriously listed among top areas to avoid, the DTES has a crime rate that is 50% higher than the Vancouver average. The 2023 Homeless Count conducted in March of 2023 revealed a total of 2,420 homeless individuals, with 605 unsheltered and 1,815 sheltered. Despite these figures, the actual number of homeless individuals is likely significantly higher, suggesting a troubling disparity between reported data and reality.

The provincial Ministry of Social Development reports that approximately 3,150 people receive income assistance in Vancouver, with those lacking a fixed address receiving an additional $75 per month. BC Housing reveals that over 3,400 individuals are currently on the waitlist for supportive housing in Vancouver. A local report highlights that around 2,000 people who use DTES welfare services have no fixed address. With more than 1,000 fewer shelter spaces than needed, hundreds are forced to be homeless.

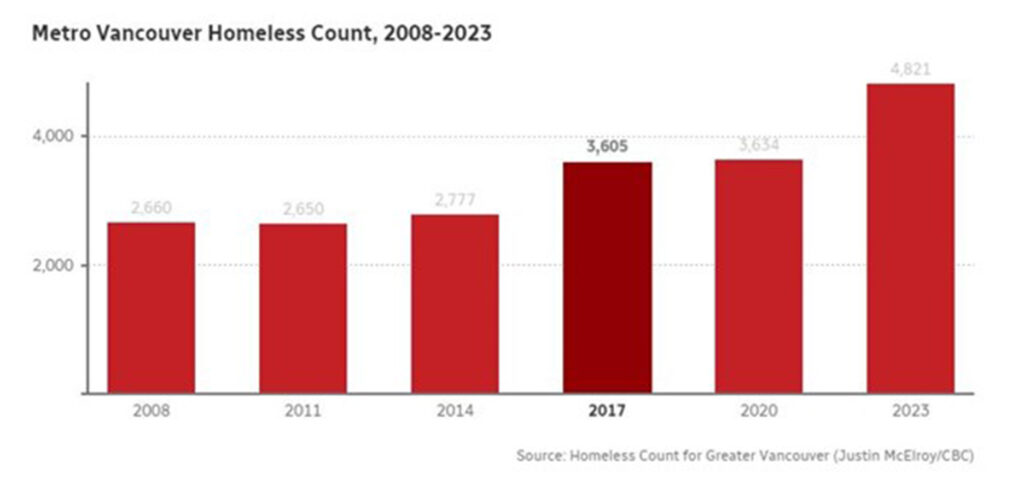

General estimates indicate that homelessness in Vancouver has surged by 32% since 2020. In 2023, 4,821 individuals were identified as experiencing homelessness, compared to 3,634 in 2020. This increase parallels a significant rise in rental costs, with the average rent for a newly listed one-bedroom apartment in Vancouver climbing by approximately 36.6 percent. This alarming trend reflects not only the callousness of authorities but also a failure in proper planning. As a result, the homelessness crisis persists unabated, compounded by escalating issues of drug overuse and prostitution.

Single-room occupancy (SRO) housing in Vancouver, primarily located in the DTES, serves low-income residents and single adults. Vancouver has about 6,567 SRO units, often considered the last stop before homelessness. These small rooms, typically 100-120 square feet, come with a bed, a wash basin, and shared hallway bathrooms. Conditions are often poor, with bed bugs, rodents, and dirt being common issues. Some buildings have community kitchens, varying but often deteriorating in maintenance quality.

Approximately half of the SROs in Vancouver are owned by non-profit housing societies, Chinese Benevolent Societies, and government entities. The remaining 3,174 units, spread across 93 privately-owned buildings, are becoming increasingly unaffordable for those relying on social assistance or basic old age benefits.

It gets worse.

Between 2020 and 2021, the province undertook an ambitious and rather absurd hotel-buying spree, investing $221 million of public funds to create 810 shelter spaces in Vancouver. This initiative included the purchase of notable hotels like the 110-room Howard Johnson Hotel at 1176 Granville Street, the 63-room Buchan Hotel at 1906 Haro Street, and the Patricia Hotel on East Hastings Street. While this move was intended as part of a broader strategy to develop a mix of affordable housing options, what did it really do?

Unfortunately, the initiative faltered due to a lack of follow-up and effective management. Without proper oversight, many of these hotels deteriorated into hotspots for drug activity and prostitution rings. The lack of structured support and adequate resources turned what was intended to be a solution into a new set of problems, exacerbating the issues of crime and safety in the very neighbourhoods the program aimed to help.

In 2017, the City of Vancouver closed the Regent and the Balmoral hotels, with 153 and 171 rooms respectively, due to severe maintenance and structural issues. Both buildings have remained vacant since. In 2023, the city, which now owns both sites, began demolishing the Balmoral. The site, along with two adjacent properties at 163 and 169 E. Hastings Street, will be redeveloped into new social housing. However, it remains unclear whether all of the new units will be affordable at the shelter rate or only a portion of them. Additionally, there is no established timeline for when these new buildings will be ready for tenants.

And what is the solution?

The City of Vancouver and the Vancouver Police Department tried something – spending a total of $548,000 to clear a homeless encampment on East Hastings Street. The money was spent to deploy dozens of officers over eight days in April 2023 to assist city crews in clearing the street’s sidewalks of tents, homeless people, and their belongings. While this solution may have made the street cleaner, it just dispersed the homeless problem and made a prevalent issue even more widespread.

For years, critics have been arguing that public funds could be spent in much better ways. Millions of dollars have been spent and the situation continues to worsen. A recent report by Vancouver community activists is warning of a major surge in homelessness by the end of the decade without a significant infusion of housing cash from senior levels of government.

Titled ‘This Isn’t Working,’ the report by the Carnegie Housing Project projects Vancouver’s homeless population could climb from about 3,150 today to more than 4,700 by 2030 due to compounding pressures on existing units that are currently affordable to the city’s lowest-income residents. The report further calls upon the government for immediate action on the following steps:

- Open 500-1,500 more shelter beds, mostly low-barrier: in Vancouver, we have about 3,100 people with no fixed address and only about 1,500 shelter beds.

- Extend leases or find modular housing sites in Vancouver: there are 144 units of nice modular homes that are currently boarded up, and more than 700 units with leases that will expire in the next few years.

- Build a tiny home village for people living in the CRAB park community: this is what the CRAB Community wants as there is no other place for them to go – it would be safer than what they have now.

- Fund the Lifeline Program proposed by the Building Community Society: this would provide support funds and housing for the most vulnerable and isolated that are living on the street. Many folks on the street have complex problems and need a lot of help, and this voluntary program could do outreach to find vulnerable individuals and help them.

- Open one or more hangout spaces: people who are homeless need a place that they can go during the day to sleep, eat, use the bathroom, shower, etc. – this is a desperate need as many existing shelters close during the day.

- Require landlords to get Residential Tenancy Branch approval and have a homeless prevention plan before evictions from social, supportive, and SRO housing. This is a popular recommendation for people who have been evicted with nowhere to go.

- Increase medical outreach in the DTES: a significant number of individuals that are living on the street need medical help but do not have transportation or knowledge on where to go and get it.

- Increase laundry and shower services in the DTES.

- Put a neighbourhood services information kiosk at Main, Hastings, and Pigeon Park.

While Metro Vancouver’s economy experiences unprecedented growth, inflation continues to surge, and the rates of working poverty and homelessness remain among the highest in Canada. Downtown Vancouver, the nation’s poorest postal code, exemplifies this stark contrast, where an indestructible community spirit persists amid immense poverty, highlighting a deep societal issue that demands urgent attention.

Despite challenges, there are solutions: increased investment in affordable housing, effective management of publicly owned housing sites, enhanced social services, and comprehensive support systems can help turn the tide and provide a pathway to a more equitable future.